A Landscape Architect’s Winter Walk — Mt. Gozen, and What a Burnt Ridge Taught Me

Walking in the mountains throughout the year is, for me, part of the design process.

Standing in the field, feeling the soil underfoot, observing the vegetation, reading the movement of water and wind with my whole body — without this accumulation of experience, I cannot translate the kotowari (the inner logic of nature) into the small space of a garden. This time, I walked the winter ridge trail from Mt. Gozen toward Otsuki. And unexpectedly, I found myself face to face with a mountain scarred by fire.

The Depth of Borrowed Scenery

Pausing on the ridge trail that winds toward the summit, I found Mt. Fuji sitting serenely beyond the crisp winter air.

In landscape design, there is a technique called shakkei — borrowed scenery — the art of drawing the landscape beyond the garden’s boundary into its composition. But what nature creates on its own exists on an entirely different dimension, in both scale and depth. The way the bare deciduous trees open up to reveal the distant mountain through their delicate winter branches — this sense of visual release is a spatial luxury that only the winter season allows.

You cannot see it when the leaves are full. Only when the trees are reduced to their bare skeletons does the depth appear.

Looking closely at the branch tips, I notice buds already beginning to swell in anticipation of spring, even in the bitter cold. These trees regulate the flow of air and water beneath the soil and hold this steep terrain in place. When I consider that this unbroken chain of activity ultimately forms the beautiful landscape before my eyes, I feel anew the weight of time embedded in a single view.

A Vertical Boundary

From the sharp summit of Mt. Gozen, I looked down to find the dense human activity of Otsuki spread out below.

What I felt was the tension and harmony produced by sheer vertical difference. The massive natural form of the mountain. The human grid of railways and buildings. At first glance, two opposites — yet this boundary between them feels to me like the original landscape from which my idea of the garden as a vessel for living was born.

When I look down at a town as a landscape architect, I find myself tracing not the arrangement of buildings, but the pathways through which water and wind travel — from mountain to town to river. The water held in these steep slopes moves underground to nourish the city and sustain the lives of its people. To build a single garden, I reminded myself in this place of altitude, is to add one small but vital breathing space to this vast cycle of circulation.

The Hand That Rewrites the Land

A golf course appeared, threading through the folds of the mountain. Its turf — a green foreign to the native vegetation — lay patchwork-like across the hillside.

When I see a landscape like this as a landscape architect, my mind moves naturally to how the original paths of water and air were reorganized by its construction, and how this land is breathing now. Large-scale regrading can appear unnatural at first glance. Yet it too is an expression of the human will to maintain and sustain a landscape.

The scale is incomparably larger than anything we encounter in garden design, but this panorama quietly puts a question to me about the weight and responsibility of the act of shaping an environment and making it work as a landscape. Gazing at the ridgeline continuing into the distance, I found myself turning over again what it truly means to align with the character of a place.

The Cycle of Fall and Renewal

Along the way, I came upon a great fallen tree, spent and horizontal, surrounded by a stretch of charred-looking ground.

As a landscape architect, what draws my attention is the groundwork this “death” lays for what comes next. The fallen tree rots back into the soil, becoming a seedbed for microorganisms that enrich the underground environment. What appears at first to be a scene of desolation is in fact a place where the earth is breathing deeply, in the midst of its own “environmental restoration,” preparing to nurture new life.

The decaying forms that tend to be avoided in a carefully designed garden are precisely where the logic of nature is most concentrated. The undulations created by the fallen tree alter the flow of water; from the nutrients that collect there, the next generation of native species will sprout. When I contemplate the immeasurable time it takes to move toward that quiet harmony, I am reminded that the landscapes we create are but one small part of this vast cycle.

Dwelling in the Vessel of the Land

Cradled in the deep folds of the mountain, a small village clusters together.

Looking at this scene as a landscape architect, it becomes clear that this is not simply a place of habitation, but a site of necessity — arrived at by topography and the logic of water. Where does the water flowing down the mountain slopes collect? Where does it create a stable, level place? Those who came before read this kotowari and shaped a place to live, as if borrowing the embrace of nature.

What connects the surrounding mountains to the village is the vegetation cultivated over long years, and the unceasing care of human hands. Respecting the mountain, coexisting with its cycles without diminishing them — this is the original landscape to which we should return when we design a garden as a vessel for living. The answer to how to translate this vast harmony into contemporary living space is inscribed in the quiet scene of this valley.

Reading the Invisible Boundaries of Vegetation

The dynamism of the mixed forest spread out below.

Looking down into this valley as a landscape architect, the invisible boundaries of vegetation — created by sunlight, water veins, and the passage of wind — begin to emerge. The slopes dense with evergreen conifers, and the bright open patches where winter light filters through deciduous broadleaves. These are not random arrangements, but the result of plants optimizing themselves over decades and centuries to the vessel of this topography.

The act of “planting a tree” in garden design is nothing less than a challenge: how to translate this grand natural order into a small space, and weave into it a sustainable cycle. Watching the gradation from ridgeline to valley floor, I pressed into myself once more the importance of creating landscapes deeply rooted in the memory of the land.

The Skeleton of the Ridge Trail

A ridge trail of exposed, dry earth. On either side, dry winter grasses reflect the pale sunlight, and the sharp shadows of upright trees cross the path.

When I trace my footsteps as a landscape architect, my awareness moves toward the hardness and aeration of the soil below. This narrow path, made by the passage of people, gently compacts the surrounding soil while also guiding the flow of rainwater — it is a boundary line. The darkened marks remaining on the ground to my right: the trace of a past fire, or evidence that the surface is being renewed? At that moment, I had not yet understood.

The season when trees have shed their leaves and the skeleton of the terrain is laid bare is the finest opportunity to observe the structure of the mountain. Hidden in this austere silence is a meticulous preparation supporting the next budding. Holding that sense of “quiet movement,” I pressed on, one step at a time.

The Void Left by a Burnt Root

When I saw the hole opening into the earth, I caught my breath.

It was the raw trace of roots burned away by fire. The ground around the charred stump had sunken in, and the network of roots that once supported life had become a hollow, boring through the earth. Fragments of charcoal scattered across the surface. The texture of completely desiccated soil. The reality that fire, with overwhelming force, had destroyed and rewritten the structure beneath the ground in an instant.

This void can no longer hold water or bind the soil. When the rains and winds come — will it accelerate collapse? Or will new sediment flow in and a different cycle begin? Staring into the fissure of this devastated surface, I felt the violent power of a moment when topography undergoes radical transformation.

Charred Forms Piercing the Sky

Looking up, blackened trees scorched by fire spread their branches toward the piercing blue of the winter sky.

Exposed to the heat of the fire, their bark seared, yet still standing vertically — their skeleton. In landscape design, when we “place a tree,” we find beauty in its form and the fullness of its foliage. But here, a tree standing at the boundary between life and death, stripped of its leaves, points its bare structure toward the heavens.

The blue needles of a pine that survived, against the black silhouette of burnt branches. In that contrast, I felt the unyielding will of this mountain — something that does not waver even after the overwhelming destruction of fire. The immovable contour of the natural world that appears when all decoration has been stripped away. I felt as though the harshness of this landscape was asking me whether I had the resolve to place it, as it is, at the core of a garden.

Exposed Root System and the Starting Point of Renewal

A great tree, burned and fallen for want of support. Its roots have heaved the earth upward, exposing the underground structure to the open air.

From a landscape design perspective, this is not simply a tree that has fallen. The upheaval of the roots creates new undulation in the surface, and air is sent into the soil that had been sealed until now. The burnt trunk and exposed roots will eventually decompose and become a seedbed for the next generation.

It is precisely this trace of brutal destruction that becomes the starting point for renewing the mountain’s vegetation and setting a stagnant environment in motion. From the shadow of the fallen tree, small shoots were already beginning to appear. Here is the site of nature’s own environmental restoration — wild and yet precise.

The Beginning of Charring and Decomposition

In the crack of a blackened, scorched trunk, a small mushroom had appeared.

The tree, whose life was ended by fire, will never again put out leaves. But its body has already shifted to become the stage for decomposers. In the work of landscape design, a tree dying marks a kind of ending. But viewed on the long timescale of this mountain, it is no more than the beginning of a process of return — enriching the soil.

Breaking through the layer of burned charcoal, fungi decompose nutrients and eventually return them to the earth. This overwhelming sense of velocity and quiet erosion. What follows in the wake of the violent upheaval of fire is not despair, but the movement of microscopic life beginning to reorganize. The coldly rational system that the natural world possesses — this small white cap was quietly embodying it.

Rising from Scorched Earth

Beside the ridge trail still bearing the scars of fire, a single young pine sapling stood straight and tall.

The surroundings are still covered in burnt soil and dead grass. But this small life is already sending its roots deep into the earth, ready to carry the next landscape. What strikes me as a landscape architect is that this is not simply “beauty” — it is the coldly precise work of life’s renewal that arrives in the wake of destruction.

The sunlight made available by the burning of the great trees that came before, and the faint nutrients brought by the ash. Drawing on these, the new growth appears as if to overcome the remnants of the previous generation. This small, upright form is the true protagonist — the one that maintains the skeleton of the mountain and weaves the green back together. Through the charred wasteland, a single firm axis of life ran clear.

The Memory and Warning of Destruction

Reading the notice posted at the trailhead, everything fell into place.

“The mountain fire that broke out in February has been extinguished, but please take care when hiking.” That single sheet quietly told me that the scorched landscape I had been walking through was not simply a natural cycle, but an incident that had occurred just recently. The dryness of the soil I had felt along the way, the charred trees, the hollow roots — all of it was directly connected to this violent event of fire.

Combined with the bear warning sign behind it, the mountain’s inherent wildness and uncontrollable nature came into sharp relief. The ferocity of nature that we tend to forget when we work with plants in the protected space of a garden. This sign, inscribed with that memory, demands of those who enter the mountain a renewed humility and clear-eyed observation.

Stacking the Stones of the Land

At the eaves of a farmhouse, a simple yet powerful stone wall.

What catches my eye as a landscape architect is that the texture of the stones perfectly matches the exposed rock I had seen in the mountains nearby. Most likely, stone quarried from this very land was used just as it came, stacked into a wall. The method of fitting together stones of uneven size and shape — reading the center of gravity of each one — is close to what we call nozurazumi (uncut stone stacking), and it produces an integration with the earth that dressed stone cannot achieve.

The soil visible in the gaps between stones, the weeds pushing up from the base — these are evidence that this wall functions not merely as a boundary, but as a breathing structure, releasing the water and air of the soil. The rugged rock face seen on the mountain, now descended to the village to become the foundation that supports people’s lives. This stone wall, which seems to have brought the character of the land down with it, contains the essence of landscape design: the simultaneous fulfillment of function and scenery.

The Receding Ridgeline

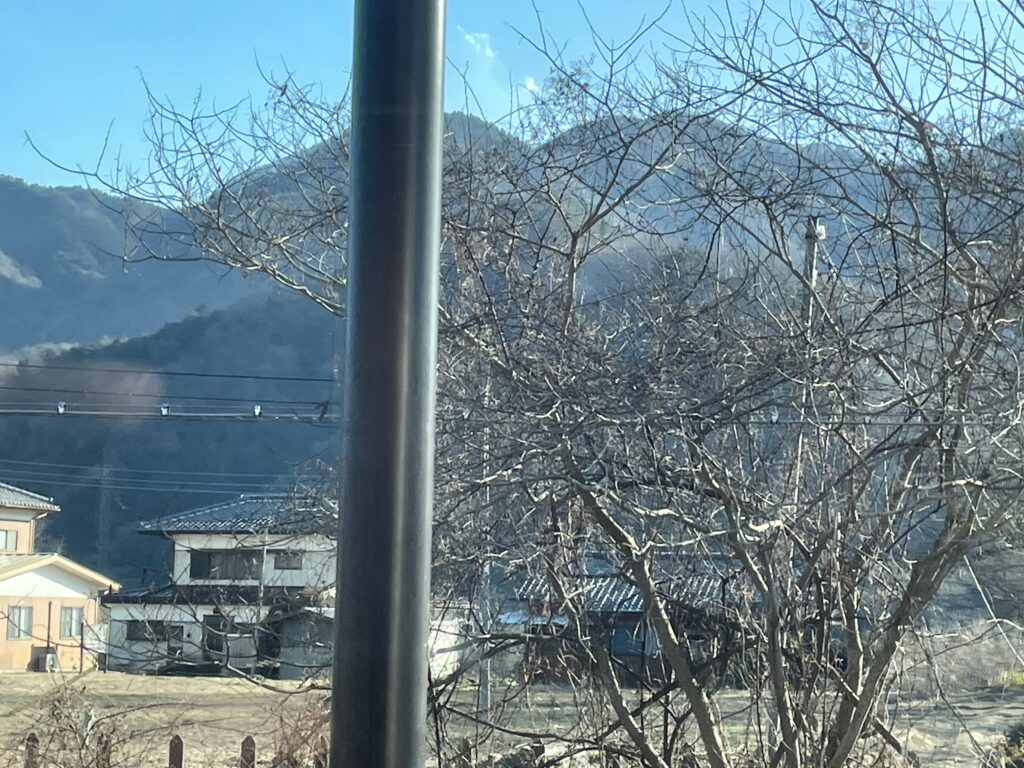

From the train window, I looked back at the ridge I had been walking just a short time ago.

The rooftops of the village spread out in the foreground, winter-bare branches. Beyond them, the silhouette of mountains carrying the wounds of fire, seated with quiet composure. After entering the mountain as a landscape architect — after feeling the smell of scorched earth and the harshness of bare rock against my skin — the view I see now is not mere background, but a living structure through which immense energy circulates.

Utility poles, power lines, houses. Human life clings to the base of the mountain, but the overwhelming logic of nature behind it all is, even now, eroding the terrain and renewing the vegetation. The young pine sapling I saw on that harsh ridge, rising from the fire’s scar. With that image of strength in my chest, I return to the landscape of the valley below.

What I brought back from the mountain is a perspective: the renewal of life.

Destruction is not an ending — it is a starting point. When something falls, air enters. When something burns, light breaks through. When something decays, the next life sprouts. To make a garden is to add, within the ring of this vast cycle, one small but vital space to breathe.

This perspective will be the unwavering core of my garden-making from here on.

Ryoji Nakayama, Ryoji Nakayama Landscape Design

Contact